In our previous blogs we talked about groin injuries and hamstring injuries. But when thinking about football injuries, it’s impossible not to think about the knee. After hamstring injuries (17%), knee injuries (12.7%) are the most common injuries in footballers. The knee is a complex joint and a variety of different knee injuries can be sustained. For example, a distinction can be made between traumatic and non-traumatic injuries. Looking at the epidemiological figures, football is mainly characterised by traumatic knee injuries, varying from bruising (2.3%) to an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture (0.9%). The latter is the greatest fear of every footballer because of the long recovery period (often around 9 months to a year).

Injury mechanism

An ACL rupture is often caused by a valgus exorotation trauma. This occurs when the lower leg is on the ground, but the knee collapses inward (knee valgus) (see the photos below). Whilst this is a high-impact injury, it is an accident just waiting to happen. It appears that an ACL rupture is most common as a result of non-contact or indirect contact playing situations (contact through the body, but not the knee). In football, about half of these injuries occur when pressing or tackling, 20% when being tackled, 16% when regaining balance after kicking and just 7% landing from a jump.

1

The occurrence of an ACL rupture when pressing/tackling. From: Della Villa, et al (2020)

Unhappy triad

The occurrence of an ACL rupture when pressing/tackling. From: Della Villa, et al (2020)

Unhappy triad

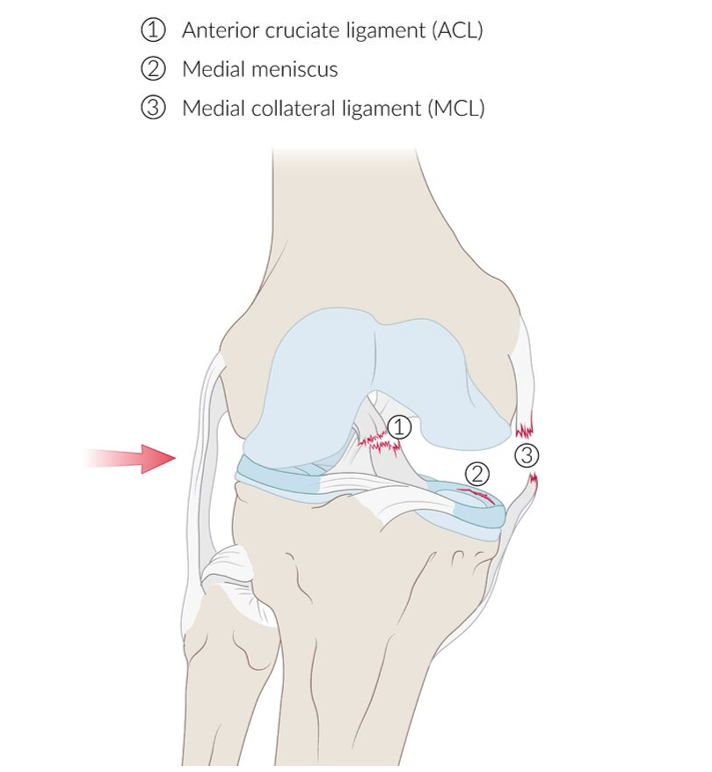

Although a torn cruciate ligament entails the longest recovery period of all football injuries, it is always hoped that the injury is not accompanied by other injuries. For example, an ACL rupture may go hand-in-hand with damage to cartilage, meniscus, the medial and/or lateral collateral ligament. A combined injury of the ACL, medial collateral ligament and the medial meniscus were described in 1950 by O’Donoghue as the “unhappy triad”. Later on, this theory was questioned by other researchers and they demonstrated that a combined injury of the ACL, medial ligament and lateral meniscus is more common.

2

Anatomie O’Donoghue unhappy triad. Uit: https://www.amboss.com/us/knowledge/Knee_ligament_injuries/

Can an unhappy triad be avoided?

Anatomie O’Donoghue unhappy triad. Uit: https://www.amboss.com/us/knowledge/Knee_ligament_injuries/

Can an unhappy triad be avoided?

The simple answer is: no. However, the literature does mention a number of risk factors that can be influenced to reduce the risk. For example, there are neuromuscular risk factors, such as weakness of the hip abductors, hip exorotators and hamstrings. We often see these muscular weaknesses in the gait. A dynamic knee valgus (for example, after landing) is characteristic of this, as also described above as an injury mechanism.

3

Get started!

Many preventative programmes focus on strengthening muscles, such as the hamstrings. Some of these programmes have been found to be effective, such as the ‘Knee Control’ programme.

4 This programme lasts 10 - 15 minutes and consists of

6 different exercises which can be integrated into the warm-up. The exercises can be performed at different levels. The exercises focus on stabilising the body’s chain as a whole (core, hip and knee) based on relatively predictable and controlled situations. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that preventative programmes are more effective if they aim to improve muscular weaknesses, at the same time as optimising the gait in a more specific context. All of the foregoing is to reduce the dynamic knee valgus and to make players more resilient in situations that require this. It is important that sufficient attention is paid to the high demands in a football-specific context.

5 Think of stabilising the knee from multidirectional movements under high pressure and disrupted balance elsewhere in the body. Additional future research will hopefully result in practical examples. Until then, programmes like ‘Knee Control’ are a good starting point.

1 Della Villa F, Buckthorpe M, Grassi A, et al, Systematic video analysis of ACL injuries in professional male football (soccer): injury mechanisms, situational patterns and biomechanics study on 134 consecutive cases. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2020;54:1423-1432.

2 Shelbourne, K. D., & Nitz, P. A. (1991). The O’Donoghue triad revisited: Combined knee injuries involving anterior cruciate and medial collateral ligament tears. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 19(5), 474–477. 9

3 Pfeifer, C. E., Beattie, P. F., Sacko, R. S., & Hand, A. (2018). RISK FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH NON-CONTACT ANTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT INJURY: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW. International journal of sports physical therapy, 13(4), 575–587.

4 Waldén M, Atroshi I, Magnusson H, Wagner P, Hägglund M. Prevention of acute knee injuries in adolescent female football players: cluster randomised controlled trial BMJ 2012; 344 :e3042

5 Dischiavi, S. L., Wright, A. A., Heller, R. A., Love, C. E., Salzman, A. J., Harris, C. A., & Bleakley, C. M. (2021). Do ACL Injury Risk Reduction Exercises Reflect Common Injury Mechanisms? A Scoping Review of Injury Prevention Programs. Sports Health.